“Cyberpunk is a warning, not an aspiration”

Introduction

I will explore the different depictions and origins of Cyberpunk and Solarpunk and talk about how the two genres differ.

Why ‘Punk’?

The word ‘punk’ is associated with rebellion, rejoicing in difference, and anarchy. This was the original meaning of the word when used in this context. However, in modern times, this has changed and the word ‘punk’ now talks of little more than speculative sub-genre. For example, Steampunk is set in a pseudo-Victorian world run on steam eg: Steamboy (2004), or Dieselpunk, which is set in a diesel run, dystopian vision e.g.: Iron Harvest (King Art Games, 2020). Interestingly, proponents of Solarpunk would still describe their genre as rebellious and thriving on diversity, although some would argue that point.

What is Cyberpunk?

Cyberpunk is a sub-genre of science fiction that originated in the literature of the early 1980s, taking inspiration from books like ‘Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?’ (Philip K. Dick, 1968). The term Cyberpunk was first coined by Bruce Bethke in his book ‘Cyberpunk’ (1982), and picked up by William Gibson in his influential novel, ‘Neuromancer’ (1984). Bruce Sterling (a founder and key proponent of the Cyberpunk literary movement)constructed the main themes of Cyberpunk to be “body invasion: prosthetic limbs, implanted circuitry, genetic alteration” and “the even more powerful theme of mind invasion: brain-computer interfaces, neurochemistry-techniques radically redefining the nature of humanity, the nature of the self” (Cyberpunk and Visual Culture, 2018). Cyberpunk itself is a criticism of late-stage capitalism, mega-corporations and human exploitation.

Book Cover

The Visual Styling of Cyberpunk

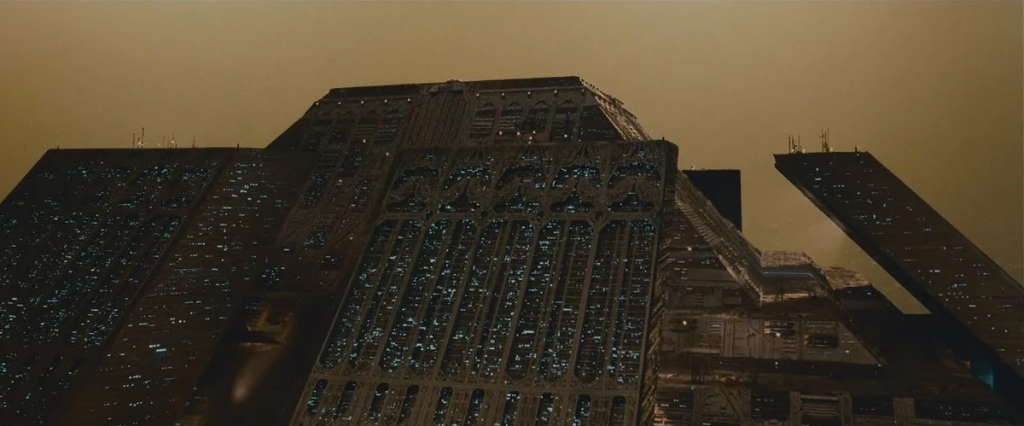

Cyberpunk takes heavy inspiration from towering, massively populated cities like Tokyo and New York. From a distance, these mega-cities look impressive and beautiful, with neon lights illuminating the night. As you get closer, you realise that nothing could be further from the truth. The architecture is often oppressively ‘Brutalist’ in form, with immoveable, bold, unaesthetic concrete shapes, drenched in a rain-induced night, devoid of human empathy. The cityscape’s only light comes from the bright greens and purples of the neon signs, illuminating the stark, inhospitable slums. “Pollution is rampant, crime is rampant and social and economic inequality is just accepted.” (Mike Pondsmith, 2020).

The film ‘Bladerunnner’ (1982), based on ‘Do Androids Dream Of Electric Sheep?’, really sets the tone and aesthetic for the entire character and environment of the Cyberpunk genre.

The visuals of Cyberpunk often mix in 1980s Japanese culture and style, due to Japan’s advanced technology. This is seen in films such as ‘Akira’ (1988) and ‘Ghost in The Shell’ (1995). Even now, the style of this genre is dependent on the neon colours of the 1980s clashing with the cold, harsh Brutalist architecture.

The Lure of Cyberpunk

The lure of Cyberpunk is the interesting juxtaposition of technological augmentation and cool, noir movie aesthetic. A good example of this is Rick Deckard from ‘Bladerunner’ (1982). Whilst he was not augmented, the ‘Replicants’ he was hunting certainly were, and the story played out in the depths of an alluring neon-lit city. The lure of Cyberpunk is so strong that you no longer have to just watch the protagonist, you can ‘be’ the protagonist and inhabit these worlds yourself thanks to the release of tabletop, roleplaying games like ‘Cyberpunk 2020’ (1988), which inspired the video game ‘Cyberpunk 2077’ (2020).

Book Cover

Book Cover

What is Solarpunk?

Solarpunk is the diametric opposite of Cyberpunk. Solarpunk was first introduced in a blog post entitled ‘Republic of Bees’ (2008). It was inspired by a new technology called ‘Beluga Skysail’, which uses wind to complement the voyage of cargo ships, to reduce their ‘dirty’ fuel consumption. Sylva (2015) points out that “it is a movement of counter-cultural hope to face the processes of accumulation, inequity, environmental degradation, control of corporations and the state over our life. Hope, then, can nourish the spaces of autonomy.” Going back further, the proto-idea of Solarpunk is embedded in Ebenezer Howard’s ethic of the ‘Garden City Movement’ from ‘Garden Cities of To-morrow’ (1898).

The Visual Styling of Solarpunk

Rather than polluted, close quarter city dwelling, Solarpunk uses clean technology to live in balance with nature. Rather than individual augments, technology is used for the good of all. Small, close-knit communities replace vast, anonymous cityscapes and natural, green buildings replace the brutalism of Cyberpunk. The entire aesthetic is “open and evolving” (Reina-Rozo, 2021), green, bright, natural and light, with elements of 1800s age of sail/frontier living. Art Nouveau, and “high tech backends with simple and elegant outputs” (Reina-Rozo, 2021).

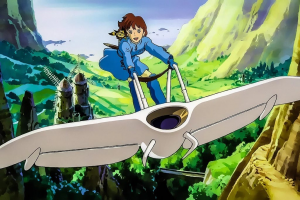

This mash-up of styles is heavily inspired by the films of Studio Ghibli, such as ‘Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind’ (1984) and ‘Castle in the Sky’ (1986). The way these films combine clean technology with the natural world lends itself to this movement and aesthetic, despite the fact that these movies are not considered to be Solarpunk films.

Possibly the best visualisation of Solarpunk is, ironically, ‘Dear Alice’ (2021). This video shows all the hallmark ideas of Solarpunk: The Ghibli aesthetic, tech being used in harmony with nature, people living in small, participatory communities and a green, renewable ethic throughout. The irony being that it was advertising a huge dairy company.

The Lure of Solarpunk

The main lure of Solarpunk is the fact that it is clean energy, that doesn’t intrude on the environment, rather it integrates with and complements the environment. It doesn’t add to global warming, and it is available to all to make their lives better.

People are already living in Solarpunk inspired communities, most notably in the Netherlands. Almere, for example, is considered the first real-world Solarpunk city. “The unique history of Almere has made it a blueprint for innovative city planning and adaptability in the face of climate change.” (Blue Labyrinth, 2023). “The neighbourhoods in Almere each have their own identity” (Blue Labyrinth, 2023), which, of course matches the mash-up vibe of Solarpunk visuals.

Conclusion

If “Cyberpunk is a warning, not an aspiration” (Mike Pondsmith, 2020) does this mean that Solarpunk is the aspiration? Solarpunk is very new and untested. We really don’t know if it will ‘actually’ work. And there’s one of the problems! True Solarpunk means that we need to reach a certain technological level (as does Cyberpunk) and that, as people we all ‘want’ to live for the greater good, putting community above our own individual needs. Another problem is that, as Solarpunk cities grow, they require ever more infrastructure. Infrastructure costs money, government costs money, and investment needs to come from the very source that Solarpunk ethics are trying to replace. As mega-corporations move in, to produce enough food, enough technology and enough housing for the people, the trap of Cyberpunk rears its ugly head. Does this mean that a Cyberpunk future is inevitable? Even now, that world is getting ever closer.

CITATIONS:

BBC News (2020) ‘Cyberpunk 2077 a “warning” about the future’, 10 December. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/newsbeat-55247702.

Dear Alice (2021) YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z-Ng5ZvrDm4.

From steampunk to solarpunk (2008) Republic of the Bees. Available at: https://republicofthebees.wordpress.com/2008/05/27/from-steampunk-to-solarpunk/.

Howard, E. (1898) Garden Cities of To-morrow. Swan Sonnenschein & Co.

Jens (2023) Almere: The first solarpunk city?, Blue Labyrinths. Available at: https://bluelabyrinths.com/2023/02/13/almere-the-first-solarpunk-city/.

Murphy, G.J. and Schmeink, L. (2018) Cyberpunk and visual culture. New York: Routledge.

Reina-Rozo, J.D. (2021) ‘Art, energy and technology: The Solarpunk Movement’, International Journal of Engineering, Social Justice, and Peace, 8(1). doi:10.24908/ijesjp.v8i1.14292.

Sylva, R. (no date) ‘Solarpunk: we are golden, and our future is bright’, Scifi Ideas. Available at: https://www.scifiideas.com/posts/solarpunk-we-are-golden-and-our-future-is-bright/.