stylised_V_real

Assignment II: Stylised -v- Realism

This article compares and contrasts how the creators of the Star Wars franchise successfully navigate the Uncanny Valley Paradox (UVP) by using stylised visuals, but their attempts at photorealistic CGI, as seen in the modern films, ultimately fall into the paradox. I will focus on the evolution of Grand Moff Tarkin and the Clone troopers and how one falls into the paradox, yet the other remains free from it despite at points, both being fully CGI.

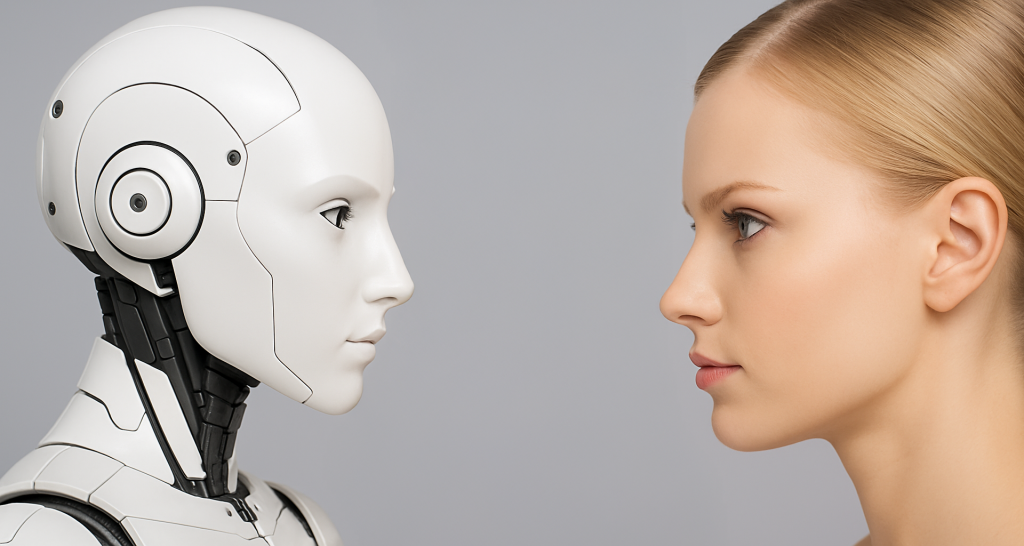

The term ‘Uncanny’, which is referred to as the ‘Uncanny Valley’, was first used by German Psychologist Ernst Jentsch in 1906. He points out that the uncanny arises from uncertainty. Sellars (2008) elaborated on this point and suggested that it becomes heightened when we ask ourselves the question, “Are the objects, which we visually perceive alive, really alive?” or “Are the objects, which we perceive as non-living, really non-living?”. This means that we are experiencing cognitive dissonance. What we are looking at is trying to look alive, in the case of highly realistic CGI visuals, but our brain is telling us that this is not true. In fact, our brain is looking for certain qualities of a human face but is unable to find them. The paradox is not about the absence of imperfections but about the presence of subtle, non-human cues that our brains detect, causing unease. For example, the skin is too clear, shiny and smooth, the hair falls just too perfectly, and the characters’ eyes have no ‘real’ depth to them, so they appear soulless.

The paradox arises when the more realistic CGI visuals try to look, the less realistic they are perceived to be. Stephanie Lay (2015), in her thesis on the UVP wrote that we “focused particularly on the dimension of ‘familiarity’ where the nature of the emotional response in the effect required greater definition.” She goes on to point out that “Brenton et al (2005) questioned whether the UVP could be linked to the concept of ‘presence’ in virtual reality.” Again, is the character ‘alive’?

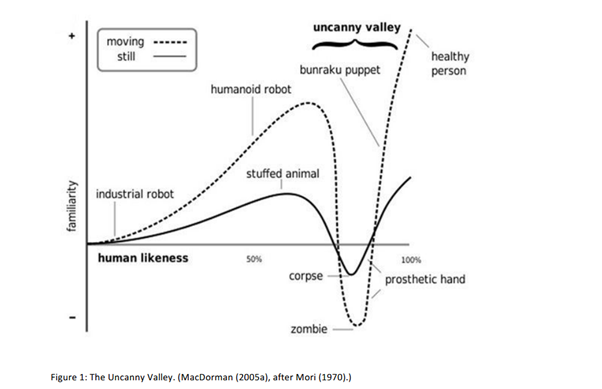

MacDorman (2005) represented the UVP in graph form:

The human likeness axis is the norm, and anything above it is familiar to us. For example, a Teddy Bear does not look like nor pretend to be human. A corpse or a zombie is very obviously human but does not fit our expected perception of what a ‘live’ human looks like, causing cognitive dissonance. This is the problem that has persisted for CGI artists and animators for many years.

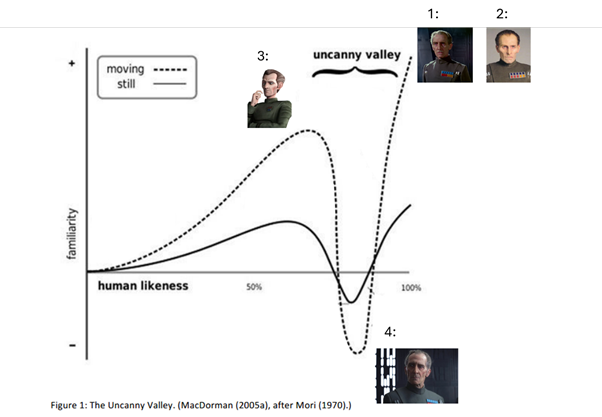

The graph below shows different versions of Grand Moff Tarkin on this scale.

Image 1 is the actor, Peter Cushing, who walks, talks, moves and breathes like a real human, with micro-expressions on his face and depth behind his eyes, so we don’t experience the UVP. This is the earliest iteration of Tarkin, many years before CGI was good enough to be able to render a human.

Even though CGI had moved on considerably by 2005, it was decided to use another real actor to play Tarkin (Image 2); a good decision as far as UVP is concerned. Peter Cushing died in 1994, so was replaced by Wayne Pygram, using make-up and prosthetics to complete the look. Whilst these techniques could introduce an element of UVP, it is greatly reduced, if not eliminated. The only dissonance introduced is the use of a different actor. However, because this movie is a prequel, we can believe that he is a younger version of Cushing.

The third image is a highly stylised and even younger version of Tarkin referencing both previous versions. Whilst the image is obviously human, the stylisation creates an interesting effect in that, in the show, the characters “… are defined as human, they cannot approach a reality beyond the traditional cartoon film character form.” (Kaba, 2012). In the Clone Wars series all the characters look stylised. The skin is painted, the hair is a solid block and, just like cartoon images, there are no micro-expressions. None of this is important in our perception, simply because we’re not expecting them from this type of stylisation. There is no cognitive dissonance, as we understand that they are not human. We are already familiar with the fact that they are simply representations of humans. This means that we do not see the mismatch between ‘alive’ and ‘dead’ to the same degree. Therefore, no UVP.

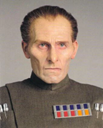

Image 4 is totally CGI rendered. It looks much better than many older human renders that obviously create UVP on movie screens. The designers have obviously spent time and energy trying to build in the imperfections that all humans have (skin pores, hair movement, etc) and provide some depth to the eyes. However, the image and its animation still lack micro-expressions, the way light bounces and scatters in a completely different way with real skin, and the true depth to the eyes which makes people real.

Despite the clone troopers being fully CGI, they do not invoke UVP because they are usually covered in armour, meaning we do not see them as human, more like humanoid robots. Even in scenes where we see their faces, they avoided UVP by having a real actor superimposed onto the CGI body. Even when they become more ‘human’ in the Clone Wars Series, we “ignore many obviously unrealistic aspects” (Low, 2001), of their stylised form. Even as we learn much more about them as ‘real people’ in the Clone Wars Series, despite being stylised and unrealistic, we start to empathise with them as emotional beings.

In conclusion, The Uncanny Valley is just as ‘alive’ now as it was in 1906. The Star Wars creators have found several novel ways to overcome UVP, with varying degrees of success. Tarkin was the central character in his scenes, which means that we are more likely to pick up on the subtle ‘mistakes’ that cause UVP. The clone troopers were mainly background or seen en masse, with a live actor for close-ups (image 5). CGI Tarkin was a step-forward in the technology and Luke Skywalker in The Book of Boba Fett (2021), their latest realistic CGI character, is a good example of what can be achieved. I believe that it is only a matter of time before CGI is virtually indistinguishable from the real thing and we no longer experience UVP in this medium.

References:

The Book of Boba Fett [TV] (2021). The Walt Disney Company.

Brenton, H. et al. (2005) ‘The Uncanny Valley: does it exist?’

Jentsch, E. (1906) On the psychology of the uncanny (1906), On the psychology of the uncanny (1906). dissertation.

Kaba, F. (2012) Hyper-Realistic Characters and the Existence of the Uncanny Valley in Animation Films. dissertation.

Lay, S. (2015) The uncanny valley effect, The Uncanny Valley Effect. thesis. Open University.

Low, G.S. (2001) Understanding Realism in Computer Games through Phenomenology. dissertation.

MacDorman , K. (2005) Androids as an Experimental Apparatus: Why Is There an Uncanny Valley and Can We Exploit It? dissertation.

Mori, M. (1970) Bukimi No Tani. dissertation.

Rogue One: A Star Wars Story [Film] (2016). Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures.

Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith [Film] (2005). Twentieth Century Fox.

Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope [Film] (1977). Twentieth Century Fox.

Star Wars: The Bad Batch [TV] (2023). The Walt Disney Company.

Star Wars: The clone wars [TV] (2008). Warner Bros.